Teaching the invisible

And letting the living find its way.

In French, there’s an expression I love: “ajuster son regard.” It literally means “to adjust one’s gaze,” but it’s not about changing your mind, it’s about subtly shifting your axis of perception. Often, nothing is visible from the outside, but inside, everything has moved.

What fascinates me is that this shift never comes from sheer will. It’s not that we refuse to see differently, it’s that willpower isn’t the right tool for this. The gaze adjusts when the mind is ready : it can come from a word, an encounter, a discomfort, a small gesture. Something that enters into friction with our internal map of the world making it vibrate differently.

And then… it starts making its way. Because some things don’t bloom instantly, they need time.

This week, I had coffee with Carla de Preval. We talked about the future. A future where we no longer speak only of AI, but of ambient intelligence, present everywhere, visible nowhere. Shaped by a handful of tech bros with a hegemonic, technocentric, self-referential vision.

A future where jobs are automated faster than they can be reimagined. Where universal basic income feels both utopian and inevitable, yet conceived not as a societal project, but as a safety net. Not distributed in the name of rights, but in the name of systemic stability. A soft anesthesia of the masses, sustained by a culture of distraction in the Pascalian sense: to keep us occupied so we don’t have to think.

We talked about what AI, in its human-mimetic form, already knows how to do: write, simulate emotion, create surrogate forms of connection. But more importantly, what it’s beginning to graze: the gray zones of the sensitive, that space between perception and experience, as its training data becomes more refined, its sensors more precise, and it begins to reach into our most intimate layers.

And soon, this won’t just be software, it will have a body. Humanoids are advancing at high speed. At WAIC, the major AI conference in Shanghai, 80 Chinese companies showcased humanoid robots this year. Only 18 did last year. What used to look like a prototype now resembles the early scaffolding of an industry of resemblance.

So I asked Carla: In a future like that, what do we still teach our children? She said, “The things you can’t see right away.” And I found that answer brilliant.

We talk a lot about hard skills, the measurable, marketable ones. We talk about soft skills, the human qualities meant to round out technical expertise. And more recently, about what I call out skills, the ability to delegate more and more to AI agents.

But there’s a whole category we’re missing. The kind you don’t learn in a course.

The kind you can’t put on a résumé. The kind you grow, quietly, through real life.

I like to think of them as vivus skills - the competencies of the living. Not skills you can automate, because they don’t come from calculation. They’re not techniques, but textures of being. They live in presence, in the quality of how we show up, in the way we connect to ourselves, to others, to the world around us.

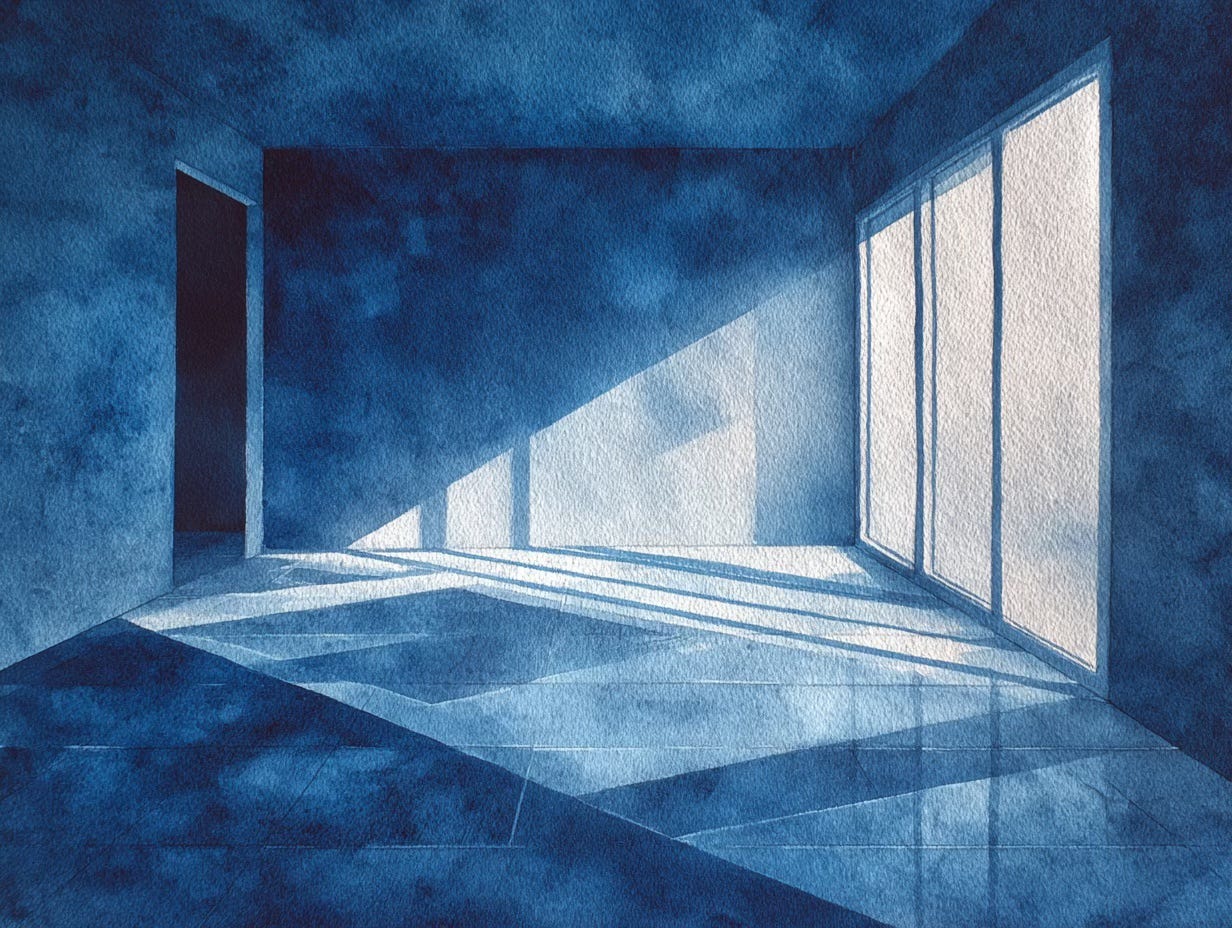

Let’s start with deep attention, in the sense Nicolas Nova gives it: the ability to observe the world without trying to capture or change it. In Exercices d’observation, inspired by ethnography and critical design, he invites us to look differently - to note repetitive gestures in a public space, to observe how light moves across a facade, to map the in-between spaces. Nothing spectacular, but a way of grounding oneself in the real world.

In L’Infra-ordinaire, Georges Perec calls for the same presence. He suggests we question not what is worth saying, but what we’ve stopped even thinking to question: “what happens when nothing happens, except time, people, cars, and clouds.” To see what is always there but no longer visible. Paving stones, elevators, the way people sit, familiar sounds, worn-out objects.

In Annie Ernaux’s The Years, writing becomes a form of attention to life itself. It flows in a continuous present, not to tell a story, but to let us perceive again. She evokes brands, songs, objects, not as personal memories, but as signs of a time. She doesn’t say “I,” she brings forth a “we.” And it’s deeply moving, because the universal rises through the ultra-ordinary. She captures what escapes spectacle - a gesture, a smell, a detail where the entire world quietly rests.

Because it’s precisely those tiny gestures, those diffuse emotions, those fragile threads - all the things that don’t show up as “signals” - that escape the models.

The invisible is what doesn’t always leave a trace, yet still alters the texture of a moment. We can model fear, but not this fear, in this person, at this exact moment in their story.

This way of sensing the subtle is a reminder of what machines can’t perceive: the quiet, almost imperceptible pulses of life. That’s where we’ll need to learn to look - not in the data, but in the weave of the living.

MD