Smombies : Captive gaze, fleeting world

If everything turns to flux, what is left to inhabit?

Smombies. A portmanteau born from the collision of smartphone and zombie—the kind of word our era invents with ease. Coined in Germany in 2015, crowned "Youth Word of the Year," it drifts in and out of language, as if unsure whether to take hold.

And yet, it names a phenomenon shaping our world far more than we admit.

Hubert Beroche doesn’t waver. He dedicates an entire book to it—264 pages of sharp analysis, set for release on March 7. Curious, I dove in during a train ride from Perpignan to Paris. And soon enough, the ideas began to flow…

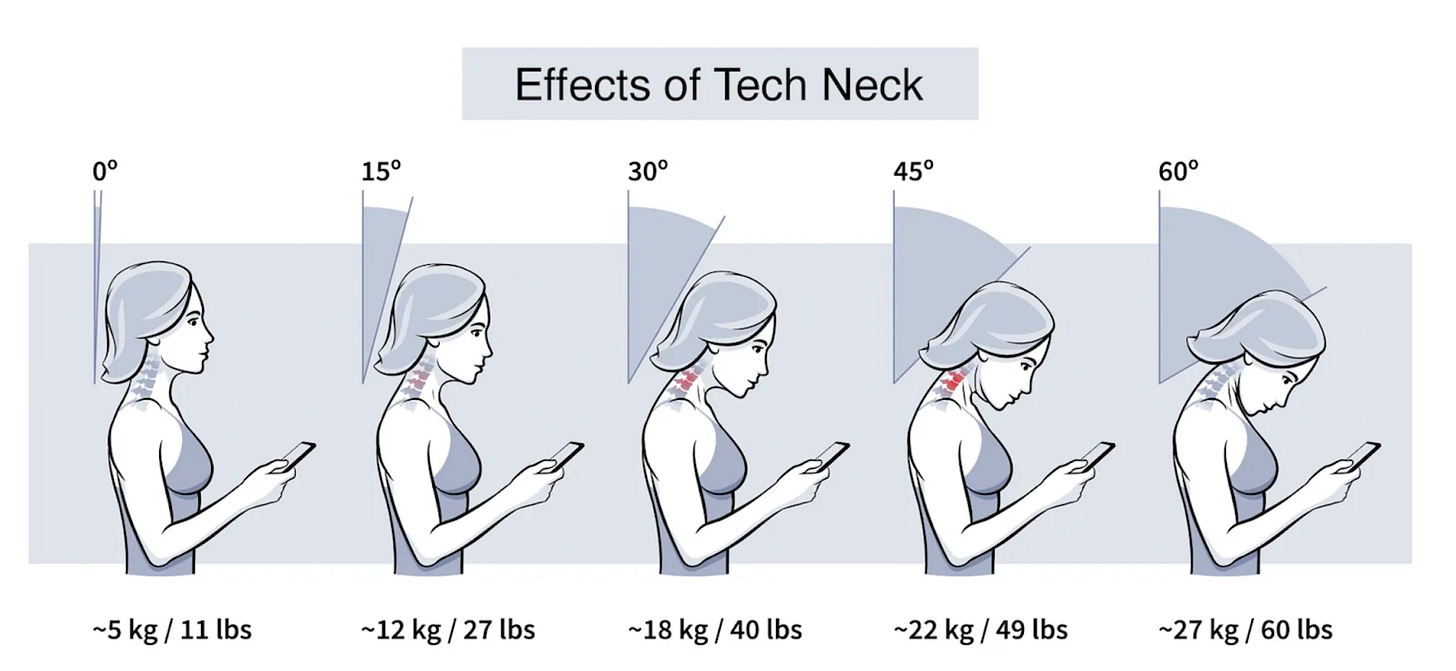

What if this seemingly trivial gesture, repeated hundreds of times a day—lowering our eyes to a screen—was more than just a habit? A movement that shapes our cities, alters our bodies, and redefines our interactions?

Look no further. In South Korea, where smartphone penetration reaches 86% in 2024, 61% of road accidents involve a pedestrian lost in their screen. So, cities adapt. Traffic lights are embedded in sidewalks, flashing from green to red to signal approaching cars.

Smombies no longer need to look up. We still do—rolling our eyes.

But this is trivial next to the deeper sociological and anthropological analysis Beroche unfolds.

Many believed social media marked the triumph of Narcissus. They were wrong. Beroche sets the record straight: most people don’t post, don’t put themselves on display. They stay silent. Drawn into the machine-zone—an endless, hypnotic current. Not a mirror, but Chronos enthroned. An insatiable ogre, devouring everything— itself, and above all, time.

The smombie is already little more than a shadow, consumed by the very light he feeds on. 390 to 750 nanometers, from violet to red. An electromagnetic wave casting its glow on his face—without him ever looking up. A specter in every sense. A ghost of himself.

In this spectral existence, blue light stands out as the perfect biological Trojan horse. It seeps into his retinas, quietly infiltrating his brain. Control doesn’t stop at his attention—it reaches deep into his very hormones.

But even ghosts have bodies. And sooner or later, the body remembers.

Tech neck, stiff shoulders, smartphone wrinkles, a hunched back. A return to the primate—without the freedom of the forest.

And it gets me thinking. Here stand the first hominids to evolve in reverse—Homo descendens rather than Homo sapiens. Darwin never foresaw that the opposable thumb, the pinnacle of evolution, would one day turn against humanity itself.

And that poses a problem. An urban problem. A societal problem.

Urbanist Jane Jacobs put it plainly: a street is safe when people watch over it. Open windows, watchful eyes. An invisible presence, yet a powerful deterrent.

But in the age of screens—who is watching?

Hitchcock made it the very core of Rear Window: that sharp, watchful gaze. Would it have had the same impact if James Stewart had been endlessly scrolling through his feed instead?

Today, this shift in gaze—from the street to the screen—is reshaping public space. Less attention. Less interaction. Less safety. Less justice.

When everyone is looking elsewhere, what remains of the truth?

We have traded the agora for the algora. And our cities are filling with absent presences.

Marc Augé spoke of non-places. We've created non-lives.

From click workers to data scientists, smombies are reshaping the urban landscape. Work moves online, but cities grow heavier. Remote work redirects the flow of people, while data centers—once tucked away in broom closets—now claim prime space in the heart of major cities.

The smombie doesn’t just cross the street; they move through infrastructures, borders, spheres of influence. Their digital omnipresence makes them both invisible and strategic. A passive tool, an active force, they have become a key cog in modern conflicts—informational, cognitive, economic.

The 2021 Capitol riot proved it: dispersed crowds can be synchronized remotely through social media.

In 2024, New Caledonia shut down TikTok to stop viral videos from fueling unrest.

Today, wars are no longer won with weapons alone, but with the control of digital flows. Power belongs to those who command the infrastructure—who shape opinion, mobilize crowds, spark crises, or silence them.

Cyberspace is now a battleground, and the smombie its most adaptable occupant.

So how do we look up again? It’s the essential question, as I’m sure you’d agree. Beroche answers it with a bold proposal: re-enchant the city.

Rethinking urban space isn’t just about resisting the pull of screens. It’s about making cities captivating again—places of attraction, surprise, and sensory engagement. Beroche draws on urban gamification and active design to imagine environments where the city itself becomes a playground.

This ties back to my reflections on digital sensitivity and the need to shift from high-tech to high-touch. Rethinking the city means learning to resonate with it again—to feel its rhythms rather than just navigate its structures. It’s about replacing nowstalgia—the longing for moments never fully lived—with poeminance: the art of inhabiting the present, allowing it to unfold like poetry over time.

At its core, awakening the senses—isn’t that just reconnecting with the soul of the world?

Helsinki’s Green Cloud perfectly embodies this vision. A fleeting artwork projected into the sky, it responded in real-time to residents’ energy consumption, turning an abstract phenomenon into a shared, tangible experience. More than a simple digital metric, the cloud made urban data visible—nudging behavior not through mandates, but through aesthetic and playful engagement.

Even the unseen infrastructure of the digital world can be integrated into this effort. In Paris, a 2024 Olympic swimming pool is partially heated by excess heat from a data center. Initiatives like this redefine the relationship between cities and technology—not as opposing forces, but as a thoughtful fusion, where digital systems embed themselves within urban life rather than erasing it.

"The post-screen city redirects attention from screens back to the streets. Instead of drowning us in information, it makes information livable."

Béroche’s vision is not some nostalgic utopia—it is a necessity in an age of attention burnout. If screens captivate, cities must enchant. If the digital world isolates, public space must reconnect.

Because a city without watchful eyes is nothing more than a backdrop.

And a backdrop is no home.

Public space is not just something we pass through.

It is something we inhabit.

And to inhabit, we must see.

MD

Unfortunately, Hubert Beroche's book is currently available only in French, with its official release set for March 7. However, you can still follow him on LinkedIn.

certainly a connexion with Carlos Moreno and his "15-Minute City concept" would be interesting to change the way to experiment the city and take benefit of physical environment instead of digital one...