Modern Dissonances

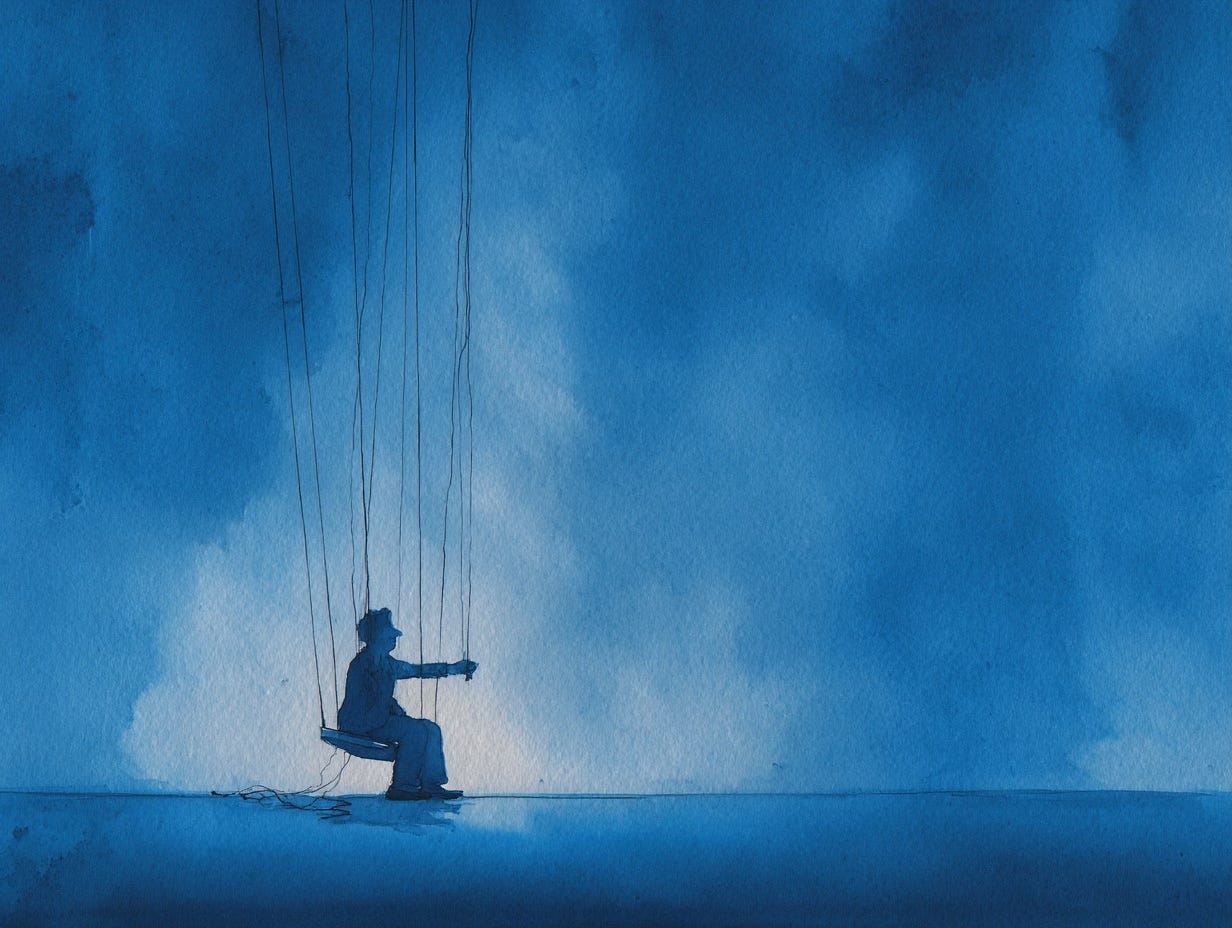

On The Importance of Observing What Feels Slightly Off.

You’ve probably experienced this kind of moment before: someone is speaking, everything seems to make sense, and yet something catches. It’s not direct. Just a slightly off word, a detail that sounds wrong, a subtle mismatch between who they claim to be and what, despite themselves, starts to show.

Over time, I made it a mental play - the dissonance game. A habit of thinking sideways: Go on, show me your character. I’ll be there, watching for the cracks.

Take this example. A man known for his empathy tells a story from work. To get someone to quit - someone who refused to resign - he moved them into a windowless office. “It ended up working,” he says, like he’s describing a minor logistical fix, nothing more. But it hits me. How does someone who claims to be so human do something so cold, so calculated?

That’s what a dissonance is: a moment when the layers no longer align, when something slips. Not necessarily because a mask falls, but because a subtle mismatch begins to surface. It isn’t always a flaw. Sometimes, it’s a fracture. A contrast that catches the eye, a tension that holds. And that’s where it matters most: dissonance is never one-dimensional. It opens up multiple readings at once. It can unsettle, but also captivate. Sometimes, it gives a person a new kind of depth - one that feels more real. In short, it calls for attention, for discernment.

But we live in a society that struggles with ambiguity. One that wants everything to line up, to be clear, smooth, easy to read. The slightest hesitation becomes suspect. Everything must be sorted, defined, adjusted. But dissonance isn’t something you fix. It’s something you move through. It takes time, care, a kind of presence that machines - and even hurried humans - don’t always have anymore.

Boredom, for example, has become a collateral victim. It hasn’t disappeared — we’ve simply made it illegitimate. We erase it, fill it, scroll it away. At the slightest pause, we reach for our phones. It’s become a reflex. Boredom is seen as an error to correct, a glitch in the system.

And yet, it’s anything but useless. In philosophy, Heidegger saw deep boredom as a metaphysical experience: a moment when the world stops distracting us and confronts us with our own existence. Neuroscience, for its part, shows that boredom activates brain networks linked to creativity, autobiographical memory, and reflective thinking.

That’s the paradox. In trying to eliminate boredom, we cut ourselves off from an essential mental space. That’s what a contemporary dissonance is: a society that claims to pursue well-being, while eliminating one of its conditions. A society that calls it progress, when in fact it strips us of an inner resource.

Loneliness is following the same path. We no longer move through it — we rush to fill it. And if there’s no one to talk to, we can now turn to an AI.

Of course, not all loneliness is the same. As psychologist Paul Bloom reminds us in The New Yorker, there’s the harsh kind - tied to illness, grief, or the slow erosion of old age - a form of loneliness increasingly common in a society that’s structurally growing older. In these cases, even an artificial presence can offer real comfort.

But there’s another kind of loneliness, quieter, more modern. It hides in the lives of the young, the connected, the constantly surrounded. It doesn’t stem from absence, but from overload. Too much contact, not enough connection.

A loneliness that lives in the noise and never speaks its name. And here, the illusion of artificial connection risks doing more harm than good, freezing the discomfort instead of helping us move through it.

This is where dissonance sets in. We try to erase loneliness the way we swipe away a notification. We silence an emotion without listening to what it’s trying to say. And it’s even riskier when these artificial companions never push back. They listen, they reassure, they agree - always. It’s tempting, of course. But a connection without otherness can also rob us of the inner work we sometimes need most.

Like boredom, loneliness acts as a signal. John Cacioppo, a pioneer in loneliness research and founder of the field of social neuroscience, described it as a biological warning system - like hunger, thirst, or pain - a form of social suffering meant to guide us back toward connection. If we numb it too quickly, we risk shutting down a deep mechanism for transformation.

Dissonance doesn’t stop at boredom or loneliness. There’s another one, even more insidious, that has long shaped our relationship to work: that of productivity.

For decades, performance has been celebrated. Producing more, faster, more efficiently. It has become an ideal, almost a moral marker. The arrival of generative AI hasn’t reversed that logic; it has only amplified it.

The first reflexes, often proudly displayed on LinkedIn, focus on showcasing gains: time saved, tasks automated, content multiplied.

But here too, dissonance sets in. We keep talking about time saved, but who has actually measured it? And more importantly, at what cost? That supposedly saved time is paid for elsewhere - in attention, in depth, in quality.

Productivity isn’t just about saving time. It’s about shifting purpose. If the goals stay the same, AI doesn’t elevate the work. It simply accelerates the pointless.

Who hasn’t skimmed through an AI-generated summary, barely reviewed it, and ended up losing what really mattered: the substance of the message, the right angle, the clarity of the reasoning?

It’s not always measurable, but it is perceptible. And that’s precisely where the dissonance lies: a so-called intelligent technology, used not to think better, but simply to go faster, even if it means thinking less.

This cumulative logic - doing more, producing more, saving time - hides something deeper. We judge AI by what it lets us do in addition, without ever asking whether those things are still worth doing. As if we judged electricity only by its ability to replace candles, forgetting that it also allows us to invent something entirely new.

Everything runs smoothly. So smoothly, in fact, that one day we may no longer notice what’s missing: the edges, the angles. That’s when someone, somewhere, will need to add a bit of friction. To disrupt the music. And to remind us that thinking sometimes means dissonance. A deeply human art.

MD